When you’re involved in real estate, an amortization schedule is your most important and helpful tool. To calculate an amortization schedule, I would recommend downloading a template from Microsoft Excel (or a similar software) and inputting your data accordingly. Below I will discuss an amortization schedule’s different variables, how you can manipulate them, and why this manipulation is important in real estate.

Variables of an Amortization Schedule:

Typically, there are three variables of an amortization schedule: (1) Loan Amount, (2) Interest Rate, and (3) Term of Loan. Let’s look at each of these in more detail.

- Loan Amount

This is the amount of money you are borrowing from a bank or lender. This will likely not be the purchase price because you’ll pay a certain down payment.

- Interest Rate

This is the percentage charged by your lender. (I think it’s important to note that if someone is lending you money, that money is valuable, and they deserve to make a profit.)

- Term of Loan

This is the duration of a loan that you are going to make regular payments on.

How do these variables work in an example? Let’s take a look:

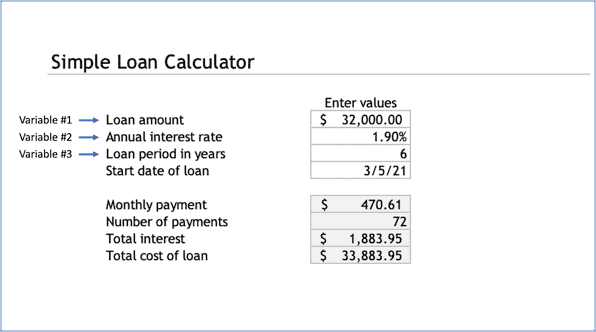

Imagine that you are going to buy a car with an original purchase price of $32,000. The car dealership is going to give you a 1.9% interest rate for a 6-year term. If you don’t put any money down upfront, your loan amount will be $32,000. After inputting each variable into your amortization schedule template (see below), your monthly payment will come out to $470.61 a month. Simple enough, right? The powerful part of an amortization schedule is when you begin to manipulate certain variables, which I will discuss next.

Variable:

Manipulation:

When it comes to financing or leveraging anything, all three variables of an amortization schedule become very important. Each time you change a variable, your monthly payment and amount of interest paid will reflect that change.

Let’s go back to the car example. If you can’t afford a $470 monthly payment, you need to think about what variables you can change in your amortization schedule in order to purchase the car. First, you should look at the original purchase price, or the amount you are going to borrow. If you lower the amount you are going to borrow and put some money down up front, you will have a greater amount of equity in the asset, which lowers your payment. The equity breakdown can be looked at in an accountant’s equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. So, if you put down $12,000 on the car, your accountant’s equation will look like this: $32,000 (purchase price) = $20,000 (borrowed) + $12,000 (equity). Increasing your equity in this way will lower your monthly payment to $294 and it will lower the total amount of interest paid over the course of the loan from $1,883 to $1,100.

The second variable you can look at is the interest rate. In our car example, a 1.9% interest rate is a monthly payment of $470 with no money down. If that interest rate was 5%, however, the monthly payment would increase to $515. If your local bank decided to charge you 5% interest and you couldn’t afford to pay $515 a month, you would need to shop for a better interest rate. You may be able to find a 2 or 3% interest rate somewhere else, which would lower your monthly payment and your overall interest payment.

Lastly, you can look at manipulating the term of the loan. Obviously, if you borrow money over a shorter amount of time, you will have fewer monthly payments, so the monthly payment will naturally be more. If you extend your term over a longer period of time, then your monthly payments will decrease, but you will have to carry your debt longer and pay more in total interest. Back to the car example: if you pay back a $32,000 loan in 1 year at a 1.9% interest rate instead of over the original 6 years, you will pay $330 in interest rather than $1,883, but your monthly payment will be close to $2,700.

How Does This Apply to Rental Houses?

When you talk about rental houses, all three of these variables come into play. The big difference is that when you look at buying a car, you work with a purchase price and payment that you can personally afford, but when you look at rent houses, the market will set the house’s gross rental rate. Personally, I operate with the principle that my debt service (interest and principal) should never be more than 60% of my gross monthly rent. I think this is a safe place to be, though there are multiple opinions on this.

So, let’s say that you are buying a house in a market that can only afford $1,000 a month in rent. This pretty much sets your payment for you if you operate by the 60% principle, making the absolute highest monthly payment you’re willing to pay $600 (there are times that you can violate this principle, but we’ll talk more about that later). After your payment, you will have $400 left for operating expenses and then profit.

Just like in the car example, you have three levers you can pull to manipulate your monthly payment and total interest amount paid, all depending on the results you want to achieve. Let’s break this down even further in an example.

Imagine you are going to buy a rental house that is priced at $120,000 and you plan on making a down payment of $20,000. Represented in an accountant’s equation, your formula will look like this: $120,000 (purchase price) = $100,000 (borrowed) + $20,000 (equity). When looking to finance the $100,000, you’ll need to visit your bank, and as much as you may want to pick your own interest rate, the bank is more or less going to dictate it for you. While the auto industry can control the interest rates of their own product, the bank is largely dependent on the market when setting an interest rate on a house, so rates will be less flexible. Right now, a typical interest rate for a rental property is about 4%, which is crazy cheap with respect to the last 30 years. The only way you can manipulate the interest rate is to shop around at other banks, which is why it’s important to have good relationships with more than one bank. If a bank knows that they are in competition for a loan, they’re probably going to sharpen their pencil a little more to secure your business (if you’re a good customer). Occasionally, a bank may be in a position to give out more funds, and they may offer great interest rates to their most predictable, dependable customers. Interest rates are negotiable, but because they are so low in today’s market, there may not be a lot of room for the bank to move.

Beyond fluctuating your loan amount through the size of your down payment, you can change your amortization schedule by manipulating the term of your loan, which may be your biggest point of influence. When I first got into rental property, it was pretty common to get a 15-year loan in rental property. In the rental house example we’re working with, this would give you a monthly payment of $739, which is outside of the 60% debt service principle. Unless you are willing to put more money down, it’s unlikely that you’ll be able to make a 15-year loan work. For today’s market, it’s more likely that you will need a 20 or 25-year loan. So, if you take a 20-year loan on $100,000 at a 4% interest rate, you’ll be at about $606 a month, which is more or less within the 60% principle. If you take a 25-year loan instead, your payment will decrease to $528, which will increase your monthly cash flow and your total interest amount paid. A 25-year term is the maximum I’ve ever done on a rental property; however, some banks have recently told me they are extending the term on rentals to 30 years. If you choose this option, your monthly payment will be $477.

So, what loan term should you choose? There are a multitude of opinions and theories that support different choices. Some people would tell you to stay as leveraged as possible and to stretch out your loan for as long as you can in order to maximize your cash flow today. Their point is that you can live on the cash flow you create and perpetually build a bigger empire. American businessman Robert Kiyosaki holds this viewpoint, saying that rich people have debt and that debt is a good thing in today’s economy.

Personally, I prefer to get out of debt sooner rather than later. To me, getting out of the rat race doesn’t mean becoming a slave to the bank because whoever holds the debt is at the top of the food chain. While you can absolutely maximize your cash flow by increasing your leverage, I don’t think it’s the best end strategy. If you pay your debt off faster to own your property sooner, you will lower your risk and eventually maximize your cash flow. Essentially, you will no longer depend on the bank because you become the bank. If you become the bank, you can truly exit the rat race.

Back to the question: which loan term should you choose? This is when you need to decide how much you feel comfortable being leveraged. If you’re just getting started, you may not know enough to completely answer this question, though you may have a gut feeling. If your goal is to get out of debt, it’s probably a good idea to try and do a shorter term. If you aren’t as concerned with debt, then you could take the longer term.

If you are older and/or unwilling to carry a lot of debt, you probably won’t be best served in a 30-year loan. So, in order to get a payment that stays within the 60% principle during a shorter loan, you’ll have to look at the amount you are borrowing and/or your interest rate. Since we already discussed the challenges of negotiating interest rates, it will probably come down to a larger down payment for you to take the shorter term. Again, all three variables affect one another and can be pulled in different ways depending on your preferences, priorities, and timeline of success.

Another Variable: Additional Principal Payments

There is another strategy for paying off a loan, which is additional principal payments. You can do this with a shorter term or a longer term. There is a conservative approach where you can extend your loan over a long period of time (30 years) and pay down on a 20-year cycle through additional principal payments. In order to do this, you will want to make sure that your loan doesn’t have prepayment penalties (unless you’re willing to pay those penalties). Additional principal payments are a great strategy, but you have to be consistent and disciplined on your payments for it to truly work.

In Summary:

- Understanding the three variables of an amortization schedule will help you get the results you desire. When you understand your options, you will know how to manipulate certain variables of your schedule. In today’s rental market, you will find the most manipulation in the amount of your down payment and the term of your loan.

- When selecting the term of your loan, make sure it lines up with your overall goals. If you’re okay with debt, you could choose a longer-term, but if you want to get out of debt, you should choose a shorter term.

- I think it’s a good idea to stick to the 60% debt service principle. If you get outside of that, you may have to put more money down or look at adjusting the term of the loan.