In the September 12, 2020 edition of the Economist, the writers (articles are anonymously written by a team of staff, thus no single author is named) consider the implications of property rights in poor countries. The article, “Who Owns What: Enforceable property rights are still far too rare in poor countries” (Economist, 2020a), makes several key observations as to why property rights are so important to the world today and the immense challenge ahead for countries to establish systems that can manage these rights. First, the writers introduce an idea from Peruvian Economist Hernando De Soto Polar, who regards land as an asset to the poor that can be borrowed against. Next, they look at that idea’s current challenges in the world’s poor countries. These challenges include structural challenges, like a lack of established government systems needed to track land, and cultural challenges, such as why women are often not allowed to be landowners. Last, the article concludes with some quick observations about land ownership.

I would like to explore each of the two main ideas and offer insights on why land ownership is an essential concept for the poorer nations of the world to consider.

De Soto’s Concept:

The Economist Staff explores the work of Hernando De Soto Polar, a renowned economist from Peru, and his 2000 book, The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. The premise of the book is that the world’s poor have unused assets that could potentially help them out of their desperate situations. Namely, the asset of the land they live on. However, the poor cannot prove they own their land due to a variety of problems stemming from a lack of formal property rights (De Soto, 2000). At the time he was writing, De Soto valued this “unclaimed land” of the poor to be at a total value of $9.3 trillion USD. Twenty years later, this would equal about $13.5 trillion dollars! De Soto says this amount is “more than 20x the value of all foreign direct aid into developing countries over the preceding decade.” Let’s examine this issue’s importance and why it could have a significant impact on the poor.

De Soto builds a case that western property rights are the bedrock for capitalism’s success. James Ely, of Vanderbilt University, explains that America’s founding fathers agreed. America’s founders saw property rights and individual freedom as being interlinked. John Adams said “Property must be secured, or liberty cannot exist.” Ely makes another assertion, “…property rights have long been linked with individual liberty… An economic system grounded on respect for private ownership tends to diffuse power and to strengthen individual autonomy from government. Property was therefore traditionally seen as a safeguard of liberty because it set limits on the reach of legitimate government” (Ely, date unknown). Also, in Edmund Morgan’s analysis of the founding fathers, The Birth of the Republic, he says the “widespread ownership of property is perhaps the most important single fact about Americans of the Revolutionary period’” (cited in Upman, 1998). David Upham writes in his article, The Primacy of Property Rights and the American Founding, that “… the right to acquire and possess private property was in some ways the most important of individual rights,” and “…persons and property are the two great subjects on which Governments are to act; and that the rights of persons, and the rights of property, are the objects, for the protection of which Government was instituted. These rights cannot well be separated” (Upman, 1998).

Private property rights, however, predated the formation of the United States. Many founding fathers leaned heavily on the ideas of John Locke and Adam Smith. It is said that Thomas Jefferson “adopted John Locke’s theory of natural rights” while writing the US Constitution (Constitutional Rights Foundation, date unknown). Locke famously said, “The only task of government is the protection of private property.” Locke argued that owning property was a “natural right” that existed before the government. Locke believed land ownership was a right given by God to all mankind, thus it was a pre-political right. However influential these two men were in discussing private property, the topic of land ownership continues to date centuries before them. As far back as the 4th century BC, Aristotle discussed property rights in response to his instructor Plato’s teachings on austerity.

So, why are property rights important for the world’s poor? Doesn’t something as abstract as property rights seem secondary to the many other needs of those suffering in poverty like food, medicine, clothing, shelter? And how could simply giving people a “paper deed” recording their “rights” translate into the $13.5 trillion dollars of value that De Soto postulates? This seems like a far stretch.

To explain this, I refer back to Aristotle. In his famous work Politics, Aristotle argues that private property ownership is superior to communal ownership in four ways: efficiency, unity, justice, and virtue (Meany, 2018). He equates private ownership to the responsibility of maintaining and improving property. Communal ownership, he argues, increases the likelihood of neglect (or possibly communal overuse). Aristotle also states that people “pay most attention to what is their own” (Meany, 2018). I have observed this principle many times in my own life. When there is joint ownership, there is often no clear chain of responsibility to who should mow the lawn, trim the bushes, or weed the garden. However, when people are free to own land, they are more likely to roll up their sleeves and dig into the tasks required to improve the property. This is a key reason that private ownership creates value. When there is individual ownership, there is a higher level of value for the individual to make the property better for themselves and their family. Individual owners get to enjoy and realize the benefit of their labor. The improvements to the property are not subject to be stolen, done away with, or damaged by someone else. It would be foolish to invest both labor and scarce resources into a parcel of land that was unstable. Property rights bring stability, which in turn releases people to action and physical improvements on the land. This basic concept becomes very important when you discuss larger capital investments in land, such as improved irrigation, higher capacity agricultural methods, construction of structures, etc. De Soto explains it this way:

“If small farmers and shanty town-dwellers had clear, legal title to their property, they could borrow money more easily to buy better seeds or start a business. They could invest in their land—by irrigating it or erecting a shop—without fear that someone might one day grab it. Property rights would make the poor richer…” (Economist, 2020a)

Again, if there was a “clear, legal title to the property,” the developing world would improve in two ways:

- Pride of ownership- The owner can feel free to improve the property without fear of losing the improvements or losing the land to someone else’s “confiscation.” This pride of ownership would lead to improvements that would increase the value of occupying the land (more food, better efficiency, improved shelters, etc…) and the production of the land (greater agricultural output).

- Property ownership opens the door to bankability- Banks or other financial institutions could establish fair lending practices based on this unutilized asset. Then, as capital is released, the property can be improved, yielding even greater value.

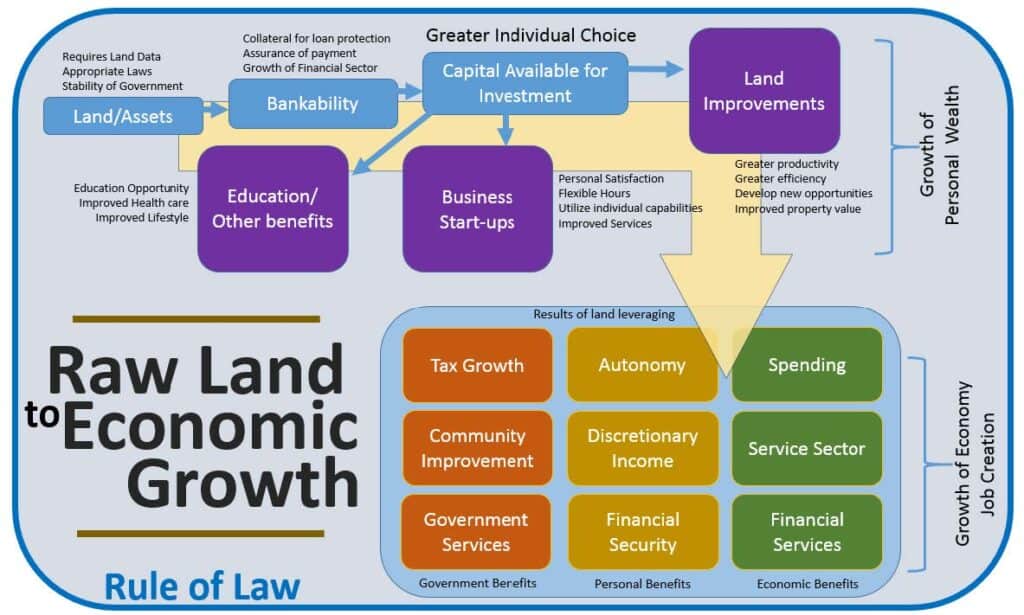

This beginning catalyst of deeding land can lead to a sequence of events that grow an entire economy. Consider what such capital means to both the individual and the larger economy. The individual can have an asset (land) that releases capital (from loans) to have options about life decisions (choices). They can buy seed to grow better crops (spending) or have the ability to start another business (investment). Or, the ability to leverage land could possibly create access for greater education or needed services. From this model, the individual property owner encounters new opportunities that they likely never had access to before. This can lead to improved quality of life, which creates freedom.

Diagram 1 – Brad Smith

Such an expenditure of capital (created by loans) then flows into the surrounding community. Capital investment in local economies leads to the creation of value for both the borrower and the extended community. This creates opportunity in various service sectors, potentially generating jobs for the village’s many other poor people. As value is created, the local economy should then have funds to create/improve a tax base and begin to offer collective government services to the people it serves. This investment could lead to policing, schools, communal water improvements, sanitation improvements, clinics, and other benefits.

See Diagram 1, an illustration of how an asset like raw land can lead to individual choice and economic improvements for an entire community. Note that this process has the opportunity to build value for both the individual and the greater community. These opportunities are dependent on a “Rule of Law” (the outside border of the diagram) that both establishes legal claim to ownership and protects the property from confiscation and damage from others. Observe that there are general economic benefits, personal benefits to the landowner, and benefits to the local community and government. Collectively, as many people engage in these activities, momentum grows until a critical mass is reached to improve the economic opportunities of the community at large.

The NGO Landesa has also agreed with this idea. In their issue brief Small Landholder Farming and Achieving Our Development Goals, they state “A thriving smallholder farm sector can be an engine for rural development…” (Landesa, 2014). This small farm can employ local people and spread economic development in the surrounding community. Simply put, reinvesting in the community has a ripple effect that doesn’t stop with the landowner. It’s this initial “unlocking of equity” that De Soto sees as so important for the start of growth and development of poor nations. However, the first step to seeing this kind of development (both of freedom and economies) is the establishment of property rights. Without property rights, the equity of the land is never unlocked to serve a greater purpose.

Structural Challenges to De Soto’s Idea:

Obviously, there are challenges to De Soto’s idea, which are not addressed in the article. First and foremost, we do not want to create a system that further injures the poor. We cannot set them up for even greater failure by allowing them to over leverage their assets. Whatever potential loan programs are created would require tight controls on lending and very clear, understandable instructions to borrowers. Also, frequent monitoring and accountability of how funds are used would be critical. Poor people may not have the greater context of how loans work and will likely need assistance in both the processing of personal choices and the maintenance of loans. Monitoring should also extend to the greater area in order to ensure corruption and abuse are not taking place.

Just as in the developed world where loans are vetted, “just having land” should not qualify all people for loans in the developing world. There should still be a thorough approval process and a critical interview of candidates. Questions regarding how funds from the loan will be used, the land’s probability of succeeding, and the risk of repayment are standard in the banking industry and would be necessary in this situation as well. These selective measures would be necessary to protect the individual and the integrity of the process. Protecting individuals from risky behaviors is part of any banking endeavor. Also, it would be important that the bank have local advisory boards to better understand local issues and challenges.

The Cato Institute has also recognized the many challenges of this situation, urging patience and remembrance that “Rome wasn’t built in a day” (O’Driscoll and Hoskins, 2003, p. 12). All involved parties require an awareness that an endeavor of this type will likely take years to succeed. This timeline includes an extended season of time required to contextualize loan procedures to appropriately fit into the greater context and history of the community being served (O’Driscoll and Hoskins, 2003, p. 12). Above all, we must diligently ensure that we would not harm the people that we intend to help.

Maybe the greatest challenge to these ideas would be the establishment of the rule of law, which is missing in many developing areas. Without a clear rule of law, the whole system crumbles. Because of this, the rule of law is the most foundational element of property rights. Locke’s assertion, “The only task of government is the protection of private property,” doesn’t mean that the government will have no other responsibilities, but that protecting private property rights is its greatest responsibility. The government must prevent corruption, protect landowner rights and property, and ensure that clear “rules of trade” are enforced for everyone’s benefit. Breaking the corrupt “path persistence” of some of these communities could be quite difficult. Generational corruption and colonial legacies favor the persistence of authoritarian rule and a lack of plurality in leadership.

This is where NGOs and other actors in development could maximize their influence. In the west, effective systems for management are common and hopefully transferable (at a minimum on a principle level) to other locations. Once these systems are effectively established, momentum should build towards law and order. Gerald O’Driscoll Jr. and Lee Hoskins’ Policy Analysis for the Cato Institute offers this insight, “…the absence of secure property rights is the cause of corruption, and the creation of private property rights would be the cure for corruption. If they could operate in an environment of secure property rights, the world’s poor would have the solution to their own plight” (O’Driscoll and Hoskins, 2003, p. 12). So as property rights are established, the rule of law potentially becomes greater and more likely. This momentum would create a new “path persistence” towards establishment of the rule of law.

The Economist article states that since the release of The Mystery of Capital in 2000, progress has been made: “Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam have all pursued vast titling projects, mapping and registering millions of land parcels.” This is definitely a hopeful sign. Along with these Asian countries, “Rwanda has mapped and titled all its territory for $7 per parcel thanks to cheap aerial photography.” However, not all countries have answered the call to move in this direction. In fact, many countries have not even started the challenge. It appears the worst concentration of land rights is in African countries. “Despite all these efforts, only 30% of the world’s people have formal titles today. In rural sub-Saharan Africa a dismal 10% do” (Economist, 2020b). This lack of defined systems and processes leads to insecurity and fear of losing homes and lands.

The World Economic Forum released a study by the Gallup Poll in July 2020, revealing that “one billion people fear losing their home” within the next five years. This study surveyed 170,000 people in 140 countries and is thought to be the largest of its kind. The study is based on the work of Prindex Global Property Rights Index, which measures viewpoints of citizens (Tabary, 2020). Prindex has partnered with the Thomas Reuters Foundation and the UK Department for International Development to “help build a world where everyone feels secure in their right to their home” (Prindex, date unknown). Indeed, these organizations are on their way to making a difference. The study goes on to reveal that residents of the Philippines (48%) and Burkina Faso (44%) show the greatest fear percentage because of rising levels of unrest and insecurity, while Singapore (4%) and Rwanda (8%) show the lowest rates of concern. Countries of Southeast Asia and Latin America did well compared with other areas, registering 21% and 19% of residents fearing loss of property (Tabary, 2020; Tabary 2019). Karol Boudreaux, of Landesa, said this should not surprise us. “Violent conflict displaces many people, and those left as well as powerful actors take advantage to seize properties…” (cited by Tabary, 2020).

De Soto’s own organization, Institute for Liberty and Democracy, acknowledged the study and said “…a lack of reliable documentation and laws, have laid the groundwork for housing insecurity” (Tabary, 2020). De Soto has also been involved in the creation of a similar index with the US-based Property Rights Alliance. The International Property Rights Index (IPRI), published annually, looks at larger views of property (including intellectual property) and various other factors to create a score for property rights and land security. Their data represents 129 countries and 94% of the world population (Levy- Carciente, 2019). In their 2019 report, the top countries were Finland (1), Switzerland (2), New Zealand (3), Singapore (4), and Australia (5). At the bottom of the index were Haiti (128), Venezuela (127), Angola (126), Bangladesh (125), and the Democratic Republic of Congo (124). For comparison, the United States ranked 12 and the United Kingdom ranked 15 (Levy-Carciente, 2019). Similar to the Prindex Study, half of the bottom 20 countries were in sub-Saharan Africa. The Economist article punctuates this by stating “only 22% of all nations have mapped and registered land in their capital cities!” This percentage drops to 4% for African countries (Economist, 2020a).

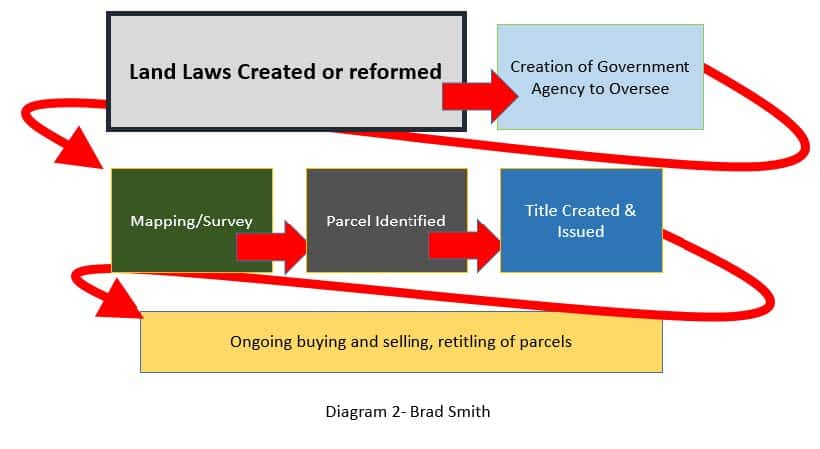

Perhaps those of us in the west underestimate the intricacy of this task? Consider how utterly complex it would be to create a system that manages property rights from ground zero. National Laws would need to change. This would require writing laws, lobbying, and passing laws, which could take years and include repatriation of lands (surely controversial). Then once the laws are passed, it would be necessary to create a government organization to implement and/or oversee the implementation, staff the organization, train, develop software, key infrastructure, and create facilities where all of this could happen, all of which would take years.

Next would be the process to map or survey the land, assign parcel numbers, record parcel numbers, create title, and issue title to the proper landowners. This would surely be a contentious process, likely to be appealed by some parties for years. Then during this entire process, land is continually bought and sold, owners die every day, and parcels change hands regularly. So, we are not exactly asking poor countries to do a simple task when we say they need to enact property rights. I cannot imagine how challenging it would be for our less developed neighbors to start this process from scratch. So, with that complexity in mind, we should have a great amount of patience and concern for countries that are working towards these goals. The Economist article quotes De Soto on this complexity: “…establishing a system of secure property rights is hard. Simply giving property-holders a title deed is not enough. A legal document is worth little if its owner cannot easily use it… All too often the institutions needed to enforce property rights smoothly, impartially and transparently are missing” (Economist, 2020a).

Cultural and Gender Challenges to De Soto’s Idea:

To further complicate these issues, local culture also plays a factor. This is especially true concerning property rights for women. Even where there are defined property rights, women are often not allowed to participate. A recent press release from the World Bank estimates that “Women in half of the countries in the world are unable to assert equal land and property rights despite legal protections…” (World Bank, 2019). Again, Karol Boudreaux says, “For women, land truly is a gateway right – without it, efforts to improve the basic rights and well-being of all women will continue to be hampered” (World Bank, 2019). She and others have aligned to create the women’s property rights organization titled Stand For Her Land, which is focused on “…closing the gap between law and practice and helping fulfill promises of gender equality.” This is a desperate issue for many. In Uganda, “stories abound of widows being [evicted from their land] by in-laws. One woman was thrown out of her home a week after her husband died in an accident…” (Economist, 2016). These incidents are not uncommon. The land rights of women across the developing world are in question. The World Bank estimates that “…close to 40 percent of the world’s economies have at least one legal constraint on women’s rights to property, limiting their ability to own, manage, and inherit land. Thirty-nine countries allow sons to inherit a larger proportion of assets than daughters and thirty-six economies do not have the same inheritance rights for widows as they do for widowers” (cited by Stone, 2018). The Council on Foreign Relations determined in a recent report, “An analysis of eight African countries found that women comprise less than one-quarter of landholders. In Latin America, the proportion of female landholders is about 20 percent, and in the Middle East and North Africa region, it is as low as 5 percent” (Stone, 2018). Again in the Economist Article, “Almost half of sub-Saharan women fear that divorce or widowhood would mean losing their fields or the roof over their heads” (Economist, 2020a). This kind of inequality is sometimes hard to do away with since it is deeply embedded in culture. Sadly, even if laws change, communities may not implement them. Unfortunately, many areas see the women in their culture as “lesser” and more “unable” to care for property than men. This leads to women and children being more at risk for poverty.

Land a Top Priority?

The World Bank meets annually to discuss the relationship between land and poverty. After the 2019 conference, it suggested that land and property rights issues be moved to the very top of the global agenda. The World Bank lists seven compelling key reasons for this decision. While I will not take the time to review all seven, I would like to summarize their thoughts (Tuck and Wael, 2019).

First, the issues of land and property rights are integral to the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals of the UN. Land issues are included in 8 targets and 12 indicators of the SDGs (Land Portal, date unknown). Land issues are tied to Goal #1 No Poverty, Goal #2 Zero Hunger, Goal #5 Gender Equality, Goal #11 Sustainability, and Goal #15 Life on the Land. Essentially, the SDG’s success by 2030 will somewhat depend on property rights reformation.

Second, the issue of property rights yields a large impact to the world’s most needy. Small amounts of land titled to poverty-stricken people has huge indications. The NGO Landesa focuses on rural poverty and the establishment of land rights. Their mission is to “secure land rights for millions of the world’s poorest, mostly rural women and men, to provide opportunity and promote social justice.” Landesa says land rights matter because “Three-quarters of the world’s poorest people live in rural areas where land is a key asset. Of those people, more than a billion lack legal rights over the land they use to survive, causing entrenched poverty cycles to persist over generations.” They argue that small landholder farms (defined by 10 hectares or less) “produce 80% of the food consumed in Africa and Asia” (Landesa, 2014). Thus, the time and effort it takes to secure land rights for small farmers has had a huge return on investment for the farmer and the greater community.

Third, property rights align with environmental and peace-keeping goals. While we are not exploring these topics in this paper, they are nonetheless very important for the wellbeing of people around the world.

In Conclusion:

De Soto’s work is not without critique. He is criticized on his methodology, assumptions, legal knowledge, and more. No doubt the sheer scope of what he addresses concerning property is bound to have many areas that need shoring up. However, over the past 20 years, De Soto has brought this issue to the forefront of many development discussions. President Bill Clinton said that De Soto was the most important living economist in the world. One can only wonder where this topic would be without his efforts.

There is a lot of work yet to be done to see property rights delivered to the developing world. Fortunately, there is much attention on this topic and many development actors focused on improvement. It is worth mentioning that Landesa has been recognized as one of the top NGOs in the world on a regular basis. Such recognition reflects the high level of support the issue of property rights has. Africa seems the furthest behind, but bright spots like Rwanda give hope that the continent can turn the corner. There are other areas of the world that lag behind, such as the South Pacific. The World Bank hopes to see 70% of the world with secure property rights by 2030. This seems daunting due to the complexity of systems required.

Not discussed at length in this article are the quality of life improvements for the person owning land. This is not so easily measured or defined in quantitative methods. What does it mean for a person to work hard all day on their own land, see the benefit of production, and provide for their families? Maybe the greatest thing private land ownership truly develops is the dignity of people. Dignity to work for themselves and no longer be dependent on others. I think this was the kind of freedom James Madison and the Founding Fathers of America had in mind.

References

1. De Soto, H. (2000) The Mystery of Capital. 1st Edition. New York: Basic Books

2. Ely, J. (date unknown), “Property Rights in American History/Hillsdale College Free Market Forum” [online], https://www.hillsdale.edu/educational-outreach/free-market-forum/2008-archive/property- rights-in-american- history/#:~:text=Second%2C%20property%20rights%20have%20long,strengthen%20individual%20auton omy%20from%20government., [accessed 11-16-2020]

3. Economist Staff (September 12, 2020), “Who owns what? Enforceable property rights are still far to rare in poor countries/The Economist” [online], https://www.economist.com/leaders/2020/09/12/who- owns-what, [accessed 11-16-2020]

4. Upman, D. (February 1, 1998), “The Primacy of Property Rights and the American Founding/Foundation for Economic Education” [online], https://fee.org/articles/the-primacy-of-property-rights-and-the- american-founding, [accessed 11-16-2020]

5. Meany, P. (July 11, 2018), “Aristotle’s Defense of Private Property: 4 Reasons Communal Property is Inferior/Foundation for Economic Education” [online], https://fee.org/articles/aristotle-s-defense-of- private-property-4-reasons-communal-property-is-inferior/, [accessed 11-16-2020]

6. O’Driscoll, G., Hoskins, L. (August 7, 2003), “Property Rights The Key to Economic Development/Cato Institute Policy Analysis” [online], https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/property-rights-key- economic-development, [accessed 11-16-2020]

7. Landesa Staff (July 2014), “Smallholder Farming and Achieving Our Development Goals/Landesa Issue Brief” [online], https://www.landesa.org/wp-content/uploads/Issue-Brief-Smallholder-Farming-and- Achieving-Our-Development-Goals.pdf, [accessed 11-16-2020]

8. Tabary, Z. (July 22, 2020), “One billion people fear losing their home, according to new poll/World Economic Forum”, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/07/homes-fear-poll-homeless-housing/, [accessed 11-16-2020]

9. Constitutional Rights Foundation Staff (unknown), “The Declaration of Independence and Natural Rights,” Constitutional Rights Foundation [online], https://www.crf-usa.org/foundations-of-our- constitution/natural- rights.html#:~:text=Among%20these%20fundamental%20natural%20rights,to%20preserve%20their%20 own%20lives, [accessed 11-16-2020]

10. Economist Staff, (September 12, 2020), “The quest for secure property rights in Africa/The Economist” [online], https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2020/09/12/the-quest-for-secure- property-rights-in-africa, [accessed 11-16-2020]

11. Tabary, Z. (March 26, 2019), “One in three fear losing homes in West and Central Africa, poll finds,” Thomson Reuters Fondation News [online], https://news.trust.org/item/20190326034911-7f27u/, [accessed 11-16-2020]

12. Prindex Staff (unkown), Home Page/Prindex [online] ,https://www.prindex.net/, [accessed 11-16- 2020]

13. Levy-Carciente, S. (2019), “International Property Rights Index 2019/Property Rights Alliance” [online], https://internationalpropertyrightsindex.org/, [accessed 11-16-2020]

14. Press Release (March 25, 2019), “Women in Half the World Still Denied Land, Property Rights Despite Laws/World Bank” [online], https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2019/03/25/women-in- half-the-world-still-denied-land-property-rights-despite-laws, [accessed 11-16-2020]

15. Unknown, (unknown), About the Campaign/Stand For Her Land [online], https://stand4herland.org/about-the-campaign/, [accessed 11-16-2020]

16. Economist Staff (July 16, 2016), “Title to Come: Property rights are still wretchedly insecure in Africa,” The Economist [online], https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2016/07/16/title- to-come, [accessed 11-16-2020]

17. Stone, M. (May 21, 2018), “A Place of Her Own: Women’s Right to Land/Council on Foreign Relations” [online], https://www.cfr.org/blog/place-her-own-womens-right-land, [accessed 11-16-2020]

18. Unknown, (unknown), “Land and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)/Land Portal” [online], https://www.landportal.org/book/sdgs, [accessed 11-16-2020]

19. Tuck, L, Wael, Z. (March 25, 2019), “7 reasons for land and property rights to be at the top of the global agenda,” World Bank Blogs [online], https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/7-reasons-land-and- property-rights-be-top-global-agenda, [accessed 11-16-2020]